Kim Chinquee, "Supper"

A response to James Gouldthorpe

The postcard is a picture of my father and his family: my grandpa at the head of the table, my grandma in her apron. My dad looks maybe five or six, my aunt is probably four. The picture’s black and white. They sit around the table. Their plates are empty.

The scene is much like the one that I grew up with. Dad at the head, Mother with her apron. My sister and me at that same table. My grandparent’s gave the farm and house to my parents after they got married.

I read books to children, of pigs and ducks and hens. They ask me about farm life. I don’t mention my father’s gun. How he shot himself after he shot my mother. How my sis and I came out of our closets, seeing things that still, I can’t believe. We walked down the stairs, around the bodies, and went to the barn to feed the heifers. My father used to kick them. He used to kick the cats that my sis and I tamed and befriended. He kicked his cows. He milked them and he fed them.

Some days I try to scribble notes. I want to write a novel.

After my parents died, our grandparents told my sister and me it was probably our fault. They sold the farm, disowned us. My aunt died last year from cancer.

In the postcard, my grandparents are smiling. My dad is stoic. My aunt smirks with her look. A casserole sits on the table, maybe some potatoes. Milk. Maybe a pork chop. A fridge is in the background, and a picture of probably my great-grandma.

My grandfather took pictures with a timer. He was ahead of his time.

I tell the children that a farm needs lots of tending. I smell the soil, manure, the stem of my roots.

Process Notes

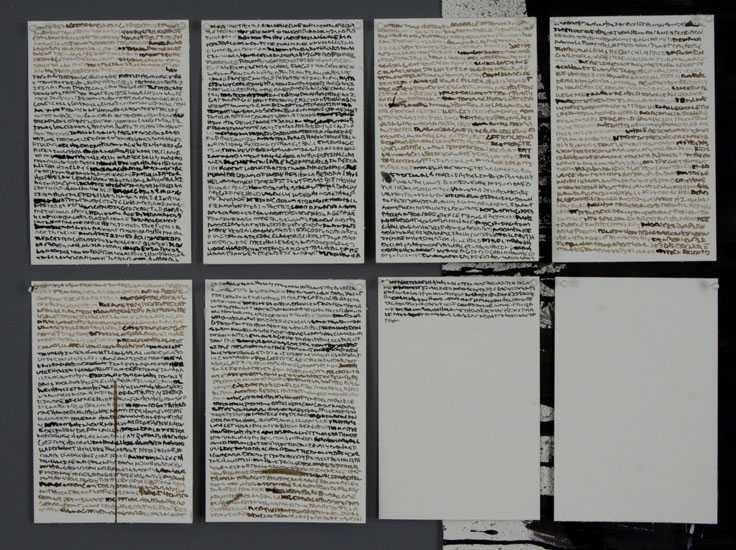

The layered images in James Gouldthorpe’s “The Great American Novel,” spoke to me like chapters in a book. The repetitions and themes, such as the image of the rifle, represented, to me, a potential violence. That, within the layered arrangement of the barren homes, the stoic nature of the humans, and the animals and meat, gave the piece a sad, quiet power that spoke in volumes.

I studied this piece for some time before I began to compose my own fiction in response. The nature of the piece reminded me of childhood, growing up on a dairy farm. My grandfather was a talented photographer ahead of his time; he had his own darkroom and experimented with light and imaging. One photo, taken at the supper table, hangs on a wall in my home. That photo is described in my piece, “Supper.”

I sensed an underlying “messiness” in “The Great American Novel,” which is perhaps in the writings included in the piece. I appreciated wanting to know what the words might be. I liked the messiness of the writing, like the messiness of life, like a tension about to erupt.

In writing “Supper,” I wanted that messiness/violence to be revealed early on. As a child, my father was either distant or explosive, and I often had this underlying fear that something really violent and crazy was about to happen—I reveal that craziness early on in “Supper,” through the violence that has occurred.

In taking my piece further, I began to fictionalize more, drawing on the images from “The Great American Novel”: the pork chop, the portrait of the great-grandmother. I intended the deadpan nature of my piece to reflect the stoic nature of “The Great American Novel.”

I also wanted to add a bit of innocence and hope to “Supper,” thence the addition of the reading to the children. It was my goal to make this protagonist an agent of her circumstance; that despite her past, she takes on a compassionate role.

Responses to James Gouldthorpe's Work

Kim Chinquee

Kim Chinquee is the author of the collections OH BABY, PRETTY, and PISTOL. Her work has appeared in several journals and anthologies including NOON, THE NATION, PLOUGHSHARES, STORYQUARTERLY, FICTION, DENVER QUARTERLY, and others. She is the recipient of a Pushcart Prize and a Henfield Prize. She lives in Buffalo, New York.