Joe Artz, "When the Sun Melted the Shadows"

A response to James Gouldthorpe

The heat that summer was so extreme it melted the shadows from the sides of houses. Black and gray rivulets of lightlessness ran across dead lawns. Shade rained down from trees and collected in pools beneath the leafy canopies. Sheep changed color, heat burning the wool black one day, sun-bleaching it white the next. Milk boiled in the bottle, turnips baked in the soil, corn roasted in the husk on the stalk. The sun helped with the butchering of hogs, scalding the bristles from the hides without the need for the farmers to dip them into boiling cauldrons. The pork, then, came roasted from the skin, ready for the carving knife, no need for the cleaver.

Tale:

Most thought the heat the result of global warming. Maggie was sure it was the work of angry gods, whom she set about to appease by baking them an angel food cake. She poured batter into a Bundt pan, and set the pan on the front step of her house to bake. She brought it in with oven mitts, let it cool, then carefully iced it with lemon meringue. She set the cake back on the step. “Here, gods,” she said, “I baked you a cake. I ate a slice to show you it’s not poisoned.” She thought the gods would float down from the sky, but instead the icing melted and the cake burst into flame. The angel food turned the color of devil’s food, then charred to carbon crumbs. Come afternoon, the crumbs were iced by shadows sloughing from under the eaves.

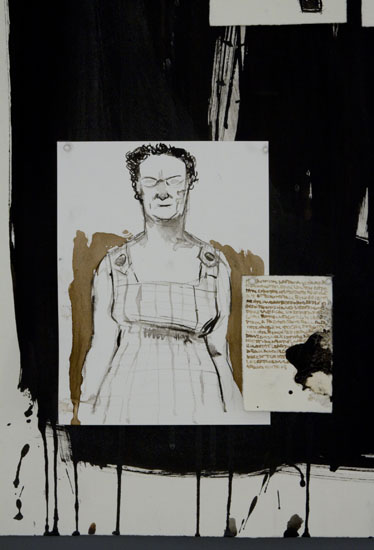

Another kind of offering occurred to Maggie. She took everything except a mirror from one wall of her living room. “Gods,” she said to the ceiling, “you’re wrong to punish everyone with this heat. I am going to give you some suggestions.” She covered the wall with people and things she considered deserving of punishment. Most of the men she knew went up on the wall, along with her hand-written notes of the things they’d said. She put up pictures of handguns, which she knew of all guns committed the most crimes, especially downtown on Friday and Saturday nights. Also a rifle with a telescopic sight because assassins used them, and an AK-47, for terrorists and Russians. She drew the guns dripping off the bluing that they were coated with to keep them from corroding. That was a suggestion to the gods of a good way to destroy all the guns.

She put up pictures of livestock because they, like men, gave off methane that scientists said contributed somehow to the heat. She put up cuts of meat because she was a vegetarian. She put up pictures of trucks because they had big hot engines and made smoke out their tail pipes. She put up two big pictures she’d drawn of her landlady, Madame Peach, and of Madame’s husband Rowley. She drew them with their glasses on, glasses as thick as the bottoms of canning jars. She drew Rowley in his favorite calico apron.

At the center of the wall, she hung a mirror just in case it was her the gods blamed.

But the heat didn’t end. She heard on the radio that piles of coal heaped beside power plants had caught fire and soon the electricity would end, and the air conditioning would go off, and everyone would die.

Even with air conditioning, the heat in her house was unbearable. One day she moved the mirror higher on the wall, raising it until the whirling blades of the ceiling fan, behind her, in the middle of the room, became visible, and the mirror reflected their cooling breeze onto her fevered, sweating face. She stood, watching, until the blades stopped and the house went dark.

Tall Tale:

Darkness came down from the sky each night to drink up the day’s liquefied shadows. Each morning, as darkness lifted, shadow precipitated into dark droplets on the grass, and lay in heavy black mists on the meadow. Drifting clouds of shadow ate the colors of the dawn. Cold fronts brought storms of shadow that rained torrents and whirled twisting black holes of wind across the land. Dark rain swelled the rivers and wetted the soil with blackness. The crops took up darkness with their roots. Fish breathed darkness through their gills. Plants converted darkness to sugars, transpired oxygenated darkness for animals to breathe, including Maggie, in her house into which shadows crept through cracks and beneath the door. The shadows rose to the outer edges of the atmosphere, touched the blackness of space, and were sucked into the void.

On that day, shadows gone, the earth cooled. Maggie woke up, went outside, and planted turnips in the jubilant earth.

Process Notes

An archaeologist by profession, much of my life has been spent studying arrangements of objects for the stories they tell about the ancient people who found the objects meaningful. Writing fiction, which I also do, is not all that different. At first sight, Gouldthorpe's artwork struck me not as story but as a collection of objects, arranged in patterns that I felt would be the obsession, and perhaps the confession, of a character I would create. Several characters later, I struck upon one who, despite the darkness of the objects she'd immersed herself in, held onto a sense of hope and light. At that point, a story emerged that I could write without becoming totally despondent, and I followed it through to create the piece you are about to read.

Responses to James Gouldthorpe's Work

Joe Artz

Joe Artz is an archaeologist when his hands are dirty and writes fiction when they are clean. His short stories have appeared in the Wapsipinicon Almanac, Daily Palette, and Every Day Fiction. He belongs to the Gray Hawk Memoir Writers, which meets fortnightly in Iowa City, Iowa