MacKenzie Dietz

A response to Maggie Jaszczak

OF WHITE THINGS STEADILY YELLOWING

Do all church basements smell like that? That cocktail of latex paint-coated cinder blocks, of crusted glue bottles, of crocheted pilgrim collars stained with eau de toilette. Of the tissue thin pages of outworn hymnals shelved by the radiator at the bottom of the stairs. Of cracked vinyl tape cinching fiberglass insulation around rusted hot water pipes. Of diapers bulging in the nursery at the end of the hall and to the right, the early elementary Sunday school room stocked with craft supplies: crispy foam balls for angels’ heads, disposable plates stapled shut around dry beans for tambourines, cotton swabs to dip in White-Out and polkadot the stars across a blue construction-paper firmament.

Of milk cartons drained and made into coin banks to save for the needy. Of salt dough for handprint-heart ornaments once, though it was almost used up by the time I got there—late after yet another fight—the last time Mom would ever try to get Dad to come with us. My heart was made of thumbprints instead.

Of the ceramic crock pot, faintly charred under all that creamed corn, and the coffee-stained Corning Ware percolator, plugged in for potluck. Of someone’s grandpa’s prosthetic eye flashing open just before the “amen” at the end of the blessing. Of someone’s uncle’s moth-eaten turtleneck sweater cuff dragging through the filling in the deviled eggs. Of the worst of the three potato casseroles curdling on the table next to the remains of the 7 Up jello mold. Of the Nelsons’ injera bread for the doro wat they’d learned to make on their mission trip to Ethiopia— you dip the injera into the stew, they’d shown us.

At the potluck for Dad’s funeral reception, the Nelsons had been glad to do another demonstration for all the relatives.

Of the Ladies’ Room’s solitary porcelain toilet bowl beaded with condensation beneath the portrait of the old bearded man giving thanks for his daily bread. Of Mom’s pearls hanging down from her neck as she peed, slumped over her bunched-up skirt and slip. Of her nylon panties digging into the flesh of her calves as she muttered, her voice low and not hers, “Well, we got him here. Over his dead body. Just like he said.” Of the accordion-pleated lace on my new black velour dress that I picked at intently so I wouldn’t have to witness her crying again, so I wouldn’t want so badly to climb into her lap, so I wouldn’t confess that I’d been so mad Dad hadn’t come see me sing in last year’s Christmas service that I’d made him get cancer that had turned his eyeballs to lemon drops and made hospital tubes grow out of his arms and made his bones get too big inside his skin and made him have to leave his body forever. Made his eyebrows all dark and wrong, now. It was all my fault. I didn’t want to find out whether the chair of Mom’s body would go on rocking me after she knew, or not.

Of someone’s grandma’s orthopedic shoes squeaking on the linoleum outside the door before she called, “Need anything in there?” and Mom forced her voice up high in reply, but it still didn’t sound like her. Of the wet sliver of bar soap on the sink.

Of the paper towels that fell in a bunch from the dispenser and chapped Mom’s nose as she swiped at it.

Of the pecan-topped clump of divinity Lindy Engels held timidly out to my mother, who let go of my hand to accept it and actually smiled. Of the jag of tooth jutting into the gap in Lindy’s gummy grin as her father smoothed the wisps of hair on her round head with his plump and gentle hand.

Of all those lilies waiting to be loaded into the station wagon and taken home to the kitchen to wilt and droop and rot, of all those petals splayed and spotted like burnt tongues in a choir of monstrous squalling mouths.

Of the pilled flannel swaddling the Baby Jesus, laid in a file box with his plastic arms thrust eternally upward, dredged back out of the storage closet again. Of the flimsy poster-board lyric sheet printed with permanent marker: “Why lies He in such mean estate / Where ox and ass are feeding? / Good Christian fear; for sinners here / The silent Word is pleading.” Of the tiny carved button on the back of Lindy’s dress as we lined up single-file and, just as we started up the stairs, she turned around and told me my father, whom she’d never met, would have a great view of the service from heaven.

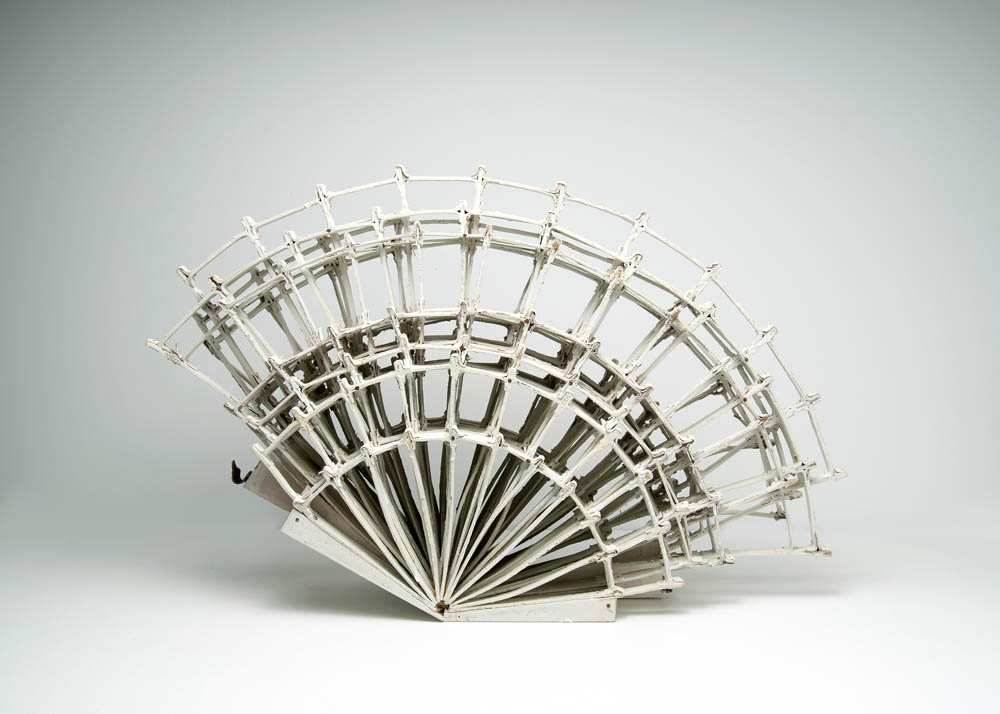

Of the memory of a bird skeleton in a glass case in the museum downtown that popped into my head the following spring when the teacher wasn’t looking and I grabbed Lindy’s scrawny forearm in both of my hands and squeezed as hard as I could, glaring into her bulging green eyes, trembling with loathing for the way her veins made a web that I could see through her skin, praying she would snap into pieces in my hands and release me from a truth I’d learned for which I had no words, and never would. Of the styrofoam egg carton cup Lindy plucked up afterwards as if nothing had happened, pasting it to the center of a construction-paper daffodil the color of a week-old bruise.

Process Notes

When I first encountered Maggie Jaszczak’s work, I felt viscerally unsettled and wanted to look away. It was akin to what I’ve felt confronting a body at a visitation: the dread of death, the compulsion to escape it.

Jaszczak's artifacts suggest lost cultural contexts while holding back clues as to what those contexts might’ve been; all we hold precious, all we comfortably know about our own lives, is equally ephemeral. Leather, hair, feathers, and milk paint used in the work remind that our very bodies are ultimately just material. Distressed textures create a sensual awareness that all matter is subject to decay.

And then there’s that rocking chair! As the mother of a young child, I am keenly aware of the ways a mother’s body is the original seat of sustenance, comfort, and safety. When I looked at that dilapidated chair and all those spoons preventing it from rocking, I saw insatiable hunger, unavailable solace, fruitless longing for protection.

So I knew I wanted to write toward ideas of mortality, deterioration, fragility, loss, and ways we organize our lives and culture in resistance of those things. No easy task! I had many false starts. Eventually I remembered that conscious abstract thought is rarely the most direct path to creativity. So I reviewed a list of words I’d made early on in response to the artworks—phrases like “avian skeleton,” “coming up against something that isn’t,” “the spreading of things to fill space,” and a host of tactile words. I then let that list in turn suggest images and memories to my mind.

The one that wouldn’t leave me alone, though I wished it would, was of a time as a child when I forcefully squeezed the arm of a younger, smaller child in my Sunday school class. I didn’t then and never have been able to understand what unutterable childhood need sparked that moment of cruelty, but once I finally accepted that the memory required a place in the story, the rest followed quickly. The question of why a child might do such a thing, the setting of the memory (which was actually full of warmth), and that eerie aura of memory itself provided the “stuff” with which to explore ideas around mortality.

It was only after I was well into the writing that it occurred to me that historically, the underground level of a church was the location of the crypt.

Responses to Maggie Jaszczak's Work

MacKenzie Dietz

MacKenzie Dietz is a fiction writer from Iowa City, IA. She has a BA in philosophy from Beloit College and studied English at the University of Kentucky. She has attended the Iowa Writers’ Workshop Summer Session and the Kenyon Review Writers’ Workshop. Her work has appeared in New Limestone Review. She lives with her musician husband and their three-year-old, a budding installation artist.