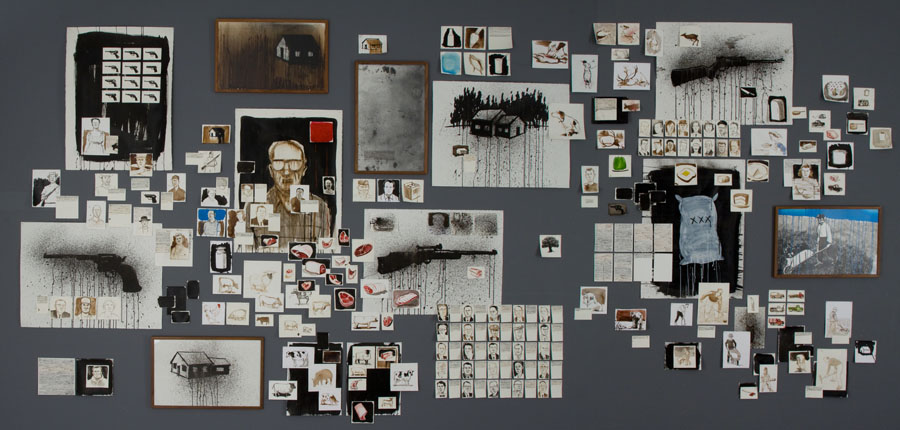

Karen Carcia, "A Series of Improvements"

A response to James Gouldthorpe

He wanted to chalk the line of a more perfect idea—and yet, notwithstanding that, he could not bridge the horizontal distances nor other matters of use to living.

The eye perplexed wrested a particular attention on molding matter into form. The eye, that great inlet of beauty, joined elegance to propriety. The wrist and arm attended to precise measurements, the edge of the saw passing over every mitered joint. A series of improvements.

Still, looking out: these vacancies. Skeins of thread, the decreasing sounds of thunder, a leaf from an ash tree, the increase he felt when watching the country dancers.

How ornamental their bones appear. Knowing their dresses should be useful. Knowing them merely as their forms. Striving to be governed by fitness and propriety, but knowing, too, pursuing is the business of our lives.

The eye, great inlet of beauty, grows inseparable to its wants. The immediate object of the eye: these forms. He joined inelegance to impropriety. No longer will we suppose: tender embrace, skeins of thread. The dresses meant to be. The eye drawn to them. How ornamental, passing over every joint, the eye perplexed to delicate life.

Process Notes

James Gouldthorpe’s The Great American Novel suggests an examination of a landscape and life, thus, I turned to William Hogarth’s 1753 The Analysis of Beauty as a source for the language in my piece. Not only did I hope to explore Gouldthorpe’s work, but also his process of repositioning, sparking a conversation between the 18th century’s process of inquiry with a 21st century collage.

Responses to James Gouldthorpe's Work

Karen Carcia

Karen Carcia is a letterpress printer and poet; she is the author of On Subjects of Which We Know Nothing (New Michigan Press, 2011).