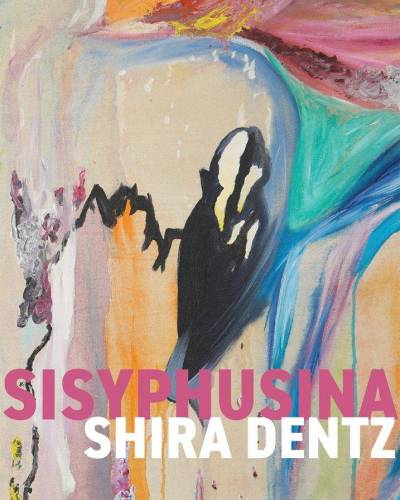

REVIEW: SISYPHUSINA

Posted on October 6, 2020

Alisha Jeddeloh Reviews "Sisyphusina," a Poetry Collection by Shira Dentz

Picture a balloon. Note the color (red, or maybe white), the smooth texture. Pull it taut and listen to the rubber groan. Now paste upon its skin a strip of newsprint, or a photocopy of your hand, or a photocopy of your hand with words written on it. Notice how the balloon has changed. How it’s still the same. Repeat the process.

Repeat.

Repeat.

Now you have an idea of what reading Shira Dentz’s Sisyphusina is like.

It’s not quite accurate to call Dentz’s latest work a poetry collection. It’s what happens when a writer runs up against the limitations of language, and instead of conceding, she expands the form into something multidimensional, shoring it up with photographs and line drawings, scatter plots and photocopies, unorthodox punctuation and font sizes, music and video, literal layers of words angled over words. Sisyphusina uses form to describe experiences for which we don’t fully have words: What it means to have a body, especially an aging body, especially an aging female body. The influence of family, the reproduction of life, the drive of life to keep going. What it means to be a human animal in all its indignity and transcendence. What we perceive, how we perceive it, how others perceive it and us.

These are weighty subjects, yet the form in Sisyphusina is playful. It breaks the reader out of the logic of language, preventing us from taking what we see and applying a grammar to it. In the process, we are forced to encounter the work directly rather than through accepted notions of communication and experience. At times it feels as if the creative process is placed on the same level as the end result, which can be a little like reading tea leaves, or a diary where the pages are out of order, or the layers of paper-mache on a balloon—it requires both the reader’s trust and intuition. “Criss-cross antlers don’t have a narrative,” Dentz tells us. “Tale carved inside a cave fanning out like a cockle shell: cave signifying echo.”

And there are so many echoes, repetitions of words and phrases and images: two balloons, tiny white hairs on a chin, roses, three different poems titled “Sisyphusina,” rolling a boulder up the hill again and again. The effect is a stream of perception, a flow between order and chaos, as in the first “Sisyphusina,” where textbook excerpts on hair in ancient Egypt are followed by this:

~

o look

one chin

haihairs of expression

a hair missed

piece to piece

~ ~ ~ air,

red me birds,

marry icons smooth

to my hairy look

what’s mere

future

This language without the clothing of logic, narration, and grammar, full of recursion and spiraling images, is reminiscent of Gertrude Stein if she’d had access to today’s technology. Like Stein’s poetry, much of the work in Sisyphusina requires a willingness on the reader’s part to submit, to leave the established structures of what is known and enter the sometimes inchoate perceptions of another. Sometimes in this process the “wax threatens to drown the wick,” as Dentz says in “The Pause Between Branches,” but this is only to be expected—perhaps even a sign of success—when daring to create a new form of communication. And why should it be easy to go beyond language, to question the rules of communication, beauty, and intimate relationships?

What makes the effort worthwhile, what all these layers and forms and textures in Sisyphusina are building toward, is this:

This trying to find a voice…

INTERNAL VOICE BLINDNESS

The near universal inability of people

to articulate the tone and personality

of the voice that forms their interior

monologue.

Remember the balloon? Now the paste has dried, hardening into a new shape. If you like, you can take a pin, or a nail, or whatever sharp thing you have lying around, and pierce the layers to pop the thin skin it was built upon. Yet in spite of witnessing its construction, you still don’t know what’s inside, not really.

Dentz leaves us a clue, though: she ends the book with a QR code to listen to “Aging Music,” a composition in collaboration with Pauline Oliveros. It is an invitation to leave language completely and enter another world, one that is haunting, difficult for the brain to order and thus can only be experienced through emotion. “Perceiving one leads to perceiving an other,” Dentz tells us. If we can perceive another’s interior, whether through words or visual art or music, who knows what can happen? The possibility is what makes it worth trying, and trying, and trying again.

Alisha Jeddeloh is a writer, the associate director of the Iowa Writers’ House, and an editor of the We the Interwoven series of bicultural anthologies. She lives in Iowa City with her family, where she is currently working on a short story cycle that explores community and belonging. As an editor, she also shapes and polishes prose for publishers and journals. She can be found at alishajeddeloh.com or @alishajeddeloh on Instagram.